After months of uncertainty and political debate, the Tees Valley Energy Recovery Facility (TVERF) looks set to move forward, following renewed commitments from the councils involved.

The proposed waste-to-energy incinerator has been the subject of controversy across the north-east of England, where it would process household rubbish from seven council areas and convert it into electricity.

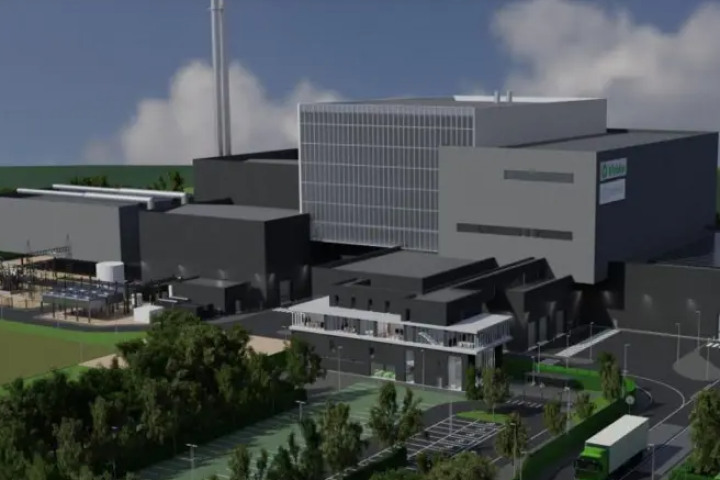

The £2bn project, led by operator Viridor, is expected to reach financial close in early 2026, marking the final stage of contractual agreement between the councils and the company. Once this milestone is achieved, full construction of the Tees Valley Energy Recovery Facility is scheduled to begin later that year.

The plant will handle up to 450,000 tonnes of residual household waste each year from Darlington, Hartlepool, Middlesbrough, Newcastle, Redcar and Cleveland, and Stockton councils.

Residual waste includes items that cannot be recycled, such as nappies, matches and certain plastics. The energy generated will be used to power the facility itself and exported to nearby electricity networks.

The Tees Valley Energy Recovery Facility will occupy a 22-acre site at Teesworks in Redcar, located on part of the former British Steel works at Grangetown. Some preliminary construction, including access point work, has already taken place. If the project proceeds as planned, the incinerator is expected to become operational in 2029.

Viridor is set to hold a 29-year contract to design, build, finance and operate the facility, with the potential for an 11-year extension.

Environmental groups have raised persistent objections to the plan. Their concerns focus on emissions, increased vehicle traffic, and the potential to undermine local recycling initiatives. Opponents have argued that pollutants and greenhouse gases from the Tees Valley Energy Recovery Facility would add to existing air quality issues in the region.

They also believe that long-term waste contracts such as this could reduce incentives for councils to invest in recycling or waste reduction.

Activists have staged multiple protests over the project, with campaigners displaying signs reading “stop the burn” and “clean air for good”. Despite the opposition, the Environment Agency granted Viridor an environmental permit in July. The agency said it was satisfied that the company had the systems in place to operate safely without harming the environment, human health, or local wildlife.

Viridor has maintained that the Tees Valley Energy Recovery Facility will not have a “significant impact” on traffic congestion. The UK Health Security Agency has also commented on the general safety of modern incinerators, stating that well-managed and regulated facilities do not pose a “significant risk to public health”. However, it added that small adverse effects could not be ruled out entirely.

The project’s future appeared uncertain earlier this year when political shifts in local councils brought renewed scrutiny.

Reform councillors in Durham initially said they would withdraw from what they described as a “horrible deal”, but later confirmed their continued participation after adjustments to the financial case.

Newcastle City Council similarly voted to pull out before its Labour cabinet reversed the decision, citing “unconscionable” penalty costs and the absence of alternative waste disposal options.

The seven partner councils will ultimately fund the project through a long-term contract with Viridor, which will recover costs via a “gate fee” charged per tonne of waste processed. The Tees Valley Energy Recovery Facility is expected to create around 700 jobs during construction and 50 permanent roles once it begins operations.